Part 1: The Collapse of The NDP

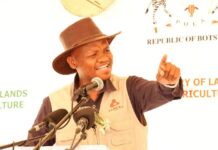

President Advocate Duma Gideon Boko, speaking on Monday, 30th June 2025, while addressing CEOs and Chairmen from all State-Owned Enterprises, announced that his Government has undertaken the bold decision to replace the traditional National Development Plan with what he titled a “National Transformational Program.” What does this change mean for the national development approach? Based on the President’s announcement, this ambitious initiative, set to be formally unveiled in October 2025, promises a more detailed, accountable, and inclusive framework for the nation’s progress.

This transition reflects a deep-seated commitment by the UDC Government to address long-standing economic challenges and foster a “New Botswana” characterised by higher productivity, diversification, and improved living standards for all citizens. The change in nomenclature from a “Plan” to a “Program” is more than a mere semantic adjustment; it signifies a fundamental re-conceptualisation of the national development agenda. This strategic reframing is intended to foster greater coherence and long-term impact across the entire spectrum of national development efforts.

The Legacy of the National Development Plan (NDP): Foundations and Fault Lines

Since gaining independence in 1966, Botswana has consistently relied on a series of National Development Plans (NDPs) to guide its social and economic progress. These plans, starting with the Transitional Plan in 1965, have historically outlined government strategies, programs, projects, and financial projections for specific periods, typically five to six years. The most recent iteration was NDP 11, which ran from April 2017 to March 2023.

Indeed, NDPs were instrumental in Botswana’s early successes, contributing to high economic growth and significant improvements in public services, such as widespread access to potable water (95% coverage) and health facilities (85% within 5km) by 2010. This impressive progress was attributed to a combination of pragmatic policymaking, prudent fiscal management, good governance, and a professional public service. However, a closer examination reveals a compelling paradox: while the foundational development planning approach of the NDPs and the initial governance structures were highly effective for a nascent economy focused on basic service provision, they proved less adaptable as the economy matured and encountered more complex, structural challenges. Botswana’s economic growth significantly slowed in the 2000s, declining to an average of 3% since 2009, and the country appears to be caught in a “middle-income trap” with declining productivity. This suggests that despite commendable early achievements, the NDP system became insufficient to navigate the evolving economic landscape and address the deeper structural issues required for sustained high-income growth and diversification, thereby creating a compelling imperative for a new, more dynamic approach like the NTP.

Despite their foundational role, NDPs have been consistently plagued by significant implementation challenges, leading to a growing consensus that the old system was insufficient for Botswana’s evolving needs. The government itself acknowledged “inadequate implementation capacity” as a major bottleneck as early as the Eighth National Development Plan (1997-2003).

Persistent Implementation Deficits

A critical flaw in the NDP system was the tendency for projects, particularly in the public sector, to be initiated based on government procurement capacity rather than a genuine assessment of national need. This “supply-driven” approach often resulted in projects that had little relevance to the nation’s actual requirements, draining public funds and diverting resources from priority areas. For instance, the construction of multiple abattoirs in Francistown and Maun, in addition to the existing one at Lobatse, led to the Botswana Meat Commission losing profitability due to increased cost structures. Similarly, undertaking major projects like the Morupule B Power Plant, the Botswana International University of Science and Technology (BIUST), and large dams within a short five-year span strained the labour supply and inflated construction prices. The construction of numerous vocational training colleges also led to an oversupply of facilities with an undersupply of students and instructors. These projects, despite significant financial cost, often sent misleading signals to the market, causing businesses to invest resources in initiatives that lacked future sustainability. Consistently, the development budget was under-spent by an average of 15-20% per year, directly denying Batswana necessary services and indicating a fundamental disconnect between planning and execution capacity.

Declining Policy Commitment and Reluctance to Reform

A concerning trend has been the government’s increasing tendency to create and adopt policies that it subsequently fails to adhere to, eroding state credibility and investor certainty. Notable examples include the abandonment of plans to privatise Air Botswana after inviting international bidders and spending funds on an international transaction advisor. Similarly, efforts to secure a private sector partner for the BIUST campus development faltered, despite two partners posting significant bonds. Furthermore, despite the Tenth National Development Plan (NDP 10) aiming to institutionalise a Results-Based Management (RBM) system, this critical reform was “quietly abandoned,” highlighting a reluctance to embrace evidence-based policymaking and accountability. Botswana’s declining rankings in industrial development, diversification, competitiveness, and ease of doing business further underscore this inertia and unwillingness to reform policies in response to a changing world.

Accountability Deficits and Governance Issues

A significant concern has been the “steady decline in accountability” across the public sector and State-Owned Corporations (SOEs), where holding politicians and public servants accountable for their actions or omissions has diminished. Oversight bodies like Parliament and the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) faced limitations in their capacity and authority to enforce accountability for poor project implementation and financial mismanagement, leading to repeated malpractice. Parliamentary inquiries into SOEs like the Botswana Meat Commission (BMC) and the Palapye Glass Project revealed systemic issues of poor corporate governance, lack of due diligence, and ineffective project management. This environment fostered a culture where implementing agents could misappropriate funds or deviate from policy goals without serious repercussions, sometimes directly opposite to intended outcomes.

Limited Private Sector Effectiveness

While NDPs, particularly NDPs 10 and 11, acknowledged and encouraged the private sector’s important role in economic growth, job creation, and diversification, the actual effectiveness of this involvement was often hampered. Challenges included a lack of clarity in the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) framework, ambiguities regarding procurement authority, and potential conflicts of interest within the PPP Unit. Moreover, concerns about poor performance by private contractors and suspicions of corruption in the construction industry further complicated effective collaboration and technology transfer.

The detailed criticisms across multiple sources reveal that the NDP’s challenges were not isolated but formed an interconnected web of failures. For example, the “supply-driven implementation” directly led to financial waste and projects that were irrelevant to national needs. This waste, combined with a “declining policy commitment,” contributed to an erosion of state credibility and investor uncertainty. Simultaneously, limited oversight by Parliament and the OAG, coupled with poor corporate governance in SOEs, created an environment where misappropriation of funds and the derailment of policy intentions by implementing agents became prevalent. The abandonment of Results-Based Management further exacerbated the lack of quality data for national decision-making, thereby hindering effective planning and accountability. This demonstrates a negative feedback loop where one failure compounded others, creating a systemic impediment to progress. This intricate interplay of challenges underscores that any new approach must be holistic, addressing these interconnected failures simultaneously rather than in isolation, to truly transform the development landscape. Breaking these entrenched negative feedback loops is essential to achieve ambitious national goals.

This is unknown to government officials.

Very informative and enticing to read all upcoming articles. Brief to the point, worthwhile points.